A Dark Moment in Central Park History – Seneca Village

It’s difficult to imagine a progress-minded city administration evicting a well-established minority community after arbitrarily paying its residents for their possessions. But that's how Central Park was made, with most newspapers cheering the removal of ''the insects.''

Seneca Village

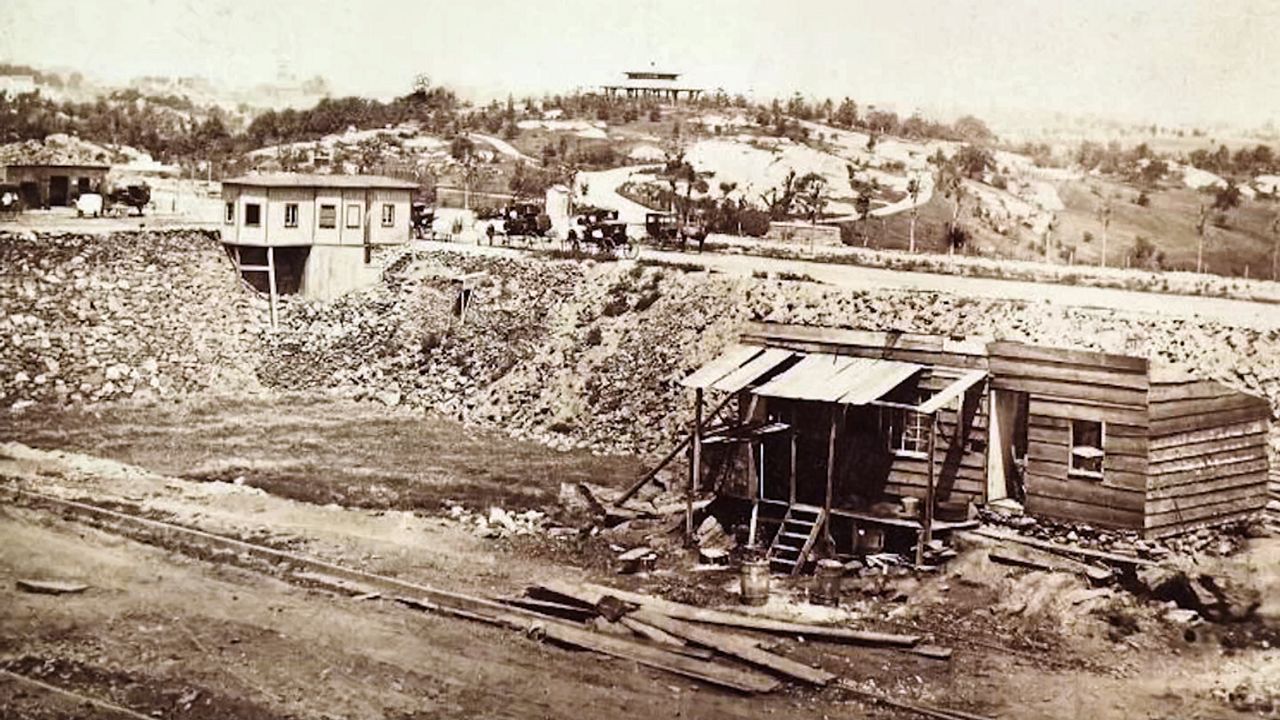

Making a great park, like making an omelet, involves a few broken shells. Seneca Village was one of the main black settlements in New York City in the 19th century. It had had 264 residents, three churches, two schools, and three cemeteries at the time of its destruction in 1885.

A largely popular exhibit named “Before Central Park: The Life and Death of Seneca Village” has since been opened by the New-York Historical Society. Said to be a “piercingly emotional show”, it brings up memories of a long-gone era. You hear voices repeating long-ago words suggesting that the park was being built mainly to benefit real estate tycoons. You stand in a church sanctuary and ponder the names of the 589 people who records show lived in Seneca Village. It makes you wonder how and why you know so little about what you’ve just seen.

Then, you think: Wait a minute. Central Park, the nation's first great municipal park, is the supreme achievement of New York City. It is where New Yorkers go to walk, to touch the grass, to play. It is where they go to breathe. Without Central Park, life in the nation's biggest city would be incalculably poorer, in some respects almost unlivable, particularly for the poor who cannot easily journey elsewhere.

How it all began

Seneca Village began in 1825 as a community of blacks, when landowners in the area, John and Elizabeth Whitehead, subdivided their land and sold it as 200 lots. Andrew Williams, a 25-year-old African-American shoe shiner, bought the first three lots for $125. Epiphany Davis, a store clerk, bought 12 lots for $578, and the AME Zion Church purchased another six lots. From there a community was born.

By the time it was razed in 1855, 30 percent of its 264 residents were Irish-American. It wasn’t an illegal, rag-tag establishment – its citizens paid taxes.

Compared to other African-Americans living in New York, residents of Seneca Village seem to have been more stable and prosperous — by 1855, approximately half of them owned their own homes. With property, ownership came other rights not commonly held by African-Americans in the City — namely, the right to vote. In 1821,

For African-Americans, Seneca Village offered the opportunity to live in an autonomous community far from the densely populated downtown. Despite New York State’s abolition of slavery in 1827, discrimination was still prevalent throughout New York City, and severely limited the lives of African-Americans. Seneca Village’s remote location likely provided a refuge from this climate. It also would have provided an escape from the unhealthy and crowded conditions of the City and access to more space both inside and outside the home.

What we know

Although we have limited knowledge of what life was like in Seneca Village, there has been ongoing work to learn more about its residents and their lives. In 2011, archaeologists from Columbia University and The City University of New York conducted a dig of the site. They uncovered artifacts such as an iron tea kettle, a roasting pan, a stoneware beer bottle, fragments of Chinese export porcelain, and a small shoe with a leather sole and fabric upper. These items have helped us piece together what life was like for the village’s residents.

Despite its short history of only 32 years, Seneca Village is understood as a tight-knit community that served as a stabilizing and empowering force in uncertain times.